We’ve spent over 20 years analysing online car buyers to understand their habits, influences and behaviours.

Using our knowledge and expertise, we help brands engage with them better.

“The biggest story in the automotive ecosystem to sell and engage with customers digitally will lie in technology enablers such as Sophus3.”

Latest Insight

03.04.2024

Chinese cars dominate latest safety ratings

Euro NCAP's latest ranking of car safety shows that Chinese brands are competitive on quality not just price.

26.03.2024

Trends to watch in 2024

Key insights from our recent webinar ‘7 trends to watch in auto digital 2024’.

07.02.2024

The Long March: Chinese car brands in Europe

Strong product, clear strategy, and rapidly increasing digital share. Why the European incumbents are sitting up and taking notice of these new market entrants.

01.02.2024

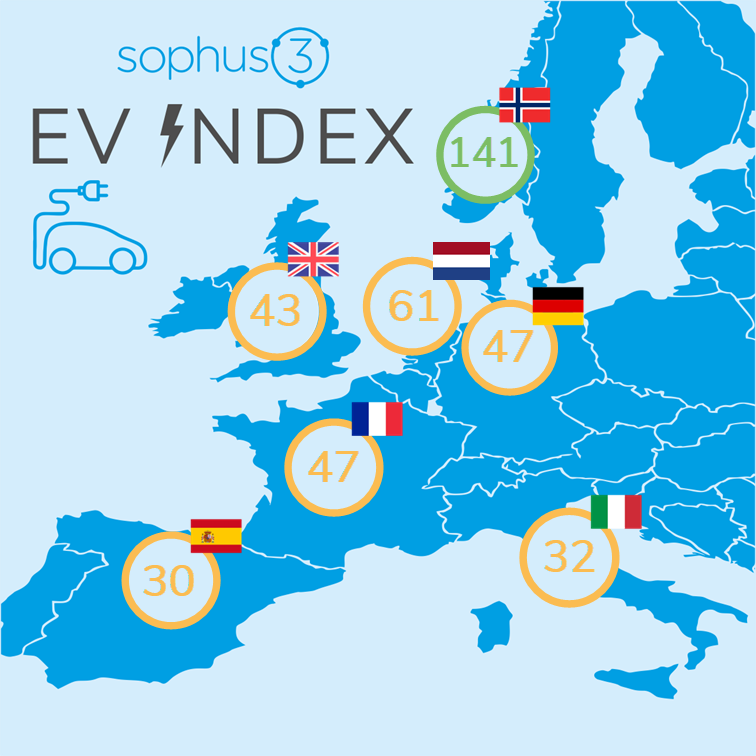

EV Index 2023 Q4: interest and sales stall

Electric vehicle sales are stalling and mass adoption in some European markets looks as far away as ever.

18.12.2023

Quiz: Can you match these Chinese brands with their models?

The new market entrants are using a confusing array of alphanumeric names for their cars.

20.06.2023

Video: Are your analytics adding business value?

We suggest three actions that can improve the insights car brands derive from their website analytics.

31.05.2023

Video: Is the marketing funnel destroying customer experience?

Prioritising customer experience is key to car brands making a success of their ecommerce channels.

16.05.2023

Video: Is your market ready for auto ecommerce?

How should car brands plan successful ecommerce rollouts?

24.04.2023

Video: What are the digital capabilities of the Chinese car brands entering Europe?

There's been much speculation about the route to market for Chinese car brands, who are turning their attention to Europe as growth stalls in China.

18.04.2023

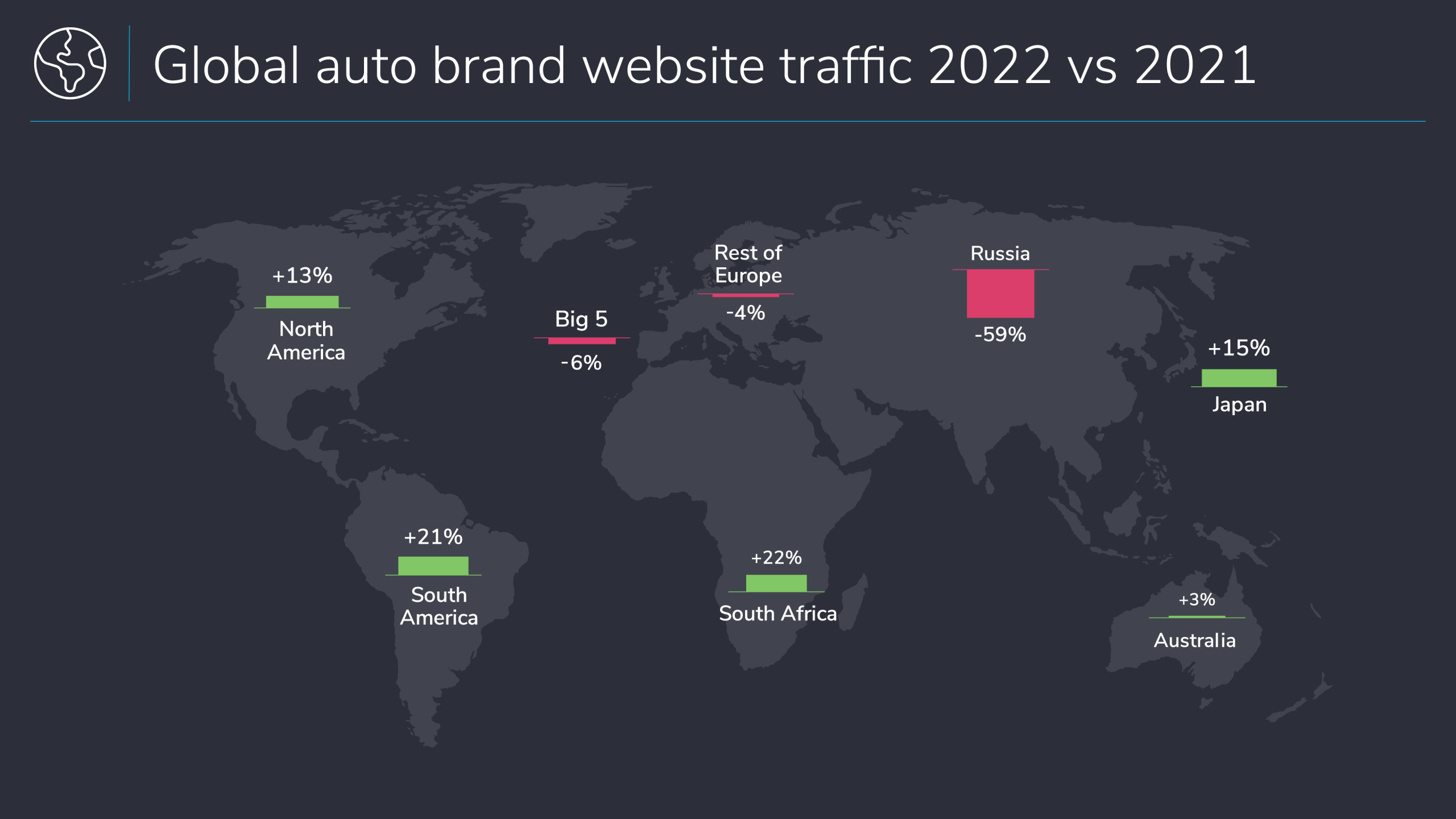

Video: Which automotive markets are growing in digital?

This extract from Sophus3’s Automotive Digital Summit 2023 looks at the differences in car-buyer interest in global regions and offers some explanation for the variations we found.

21.03.2023

White Paper: Digital Car Buyer in Numbers 2023

Data and insight from Sophus3's Automotive Digital Summit 2023.

21.03.2023

Video: What works best in automotive ecommerce?

In this 10-minute video, we analyse data from hundreds of automotive brand websites to reveal what works best in automotive ecommerce.

08.12.2022

How ‘digital’ are Chinese challenger auto brands?

The second part of Sophus3's paper on Chinese OEMs in Europe surveys and comments on their digital capabilities.

27.11.2022

Chinese auto brands coming to Europe: full report

This first part of Sophus3's paper on the entrance of Chinese car makers into Europe looks at the reasoning and strategy behind their move.

08.06.2022

How to put the ‘human’ into auto ecommerce

Watch the latest episode from Sophus3's Automotive Digital Summit 2022.

31.03.2022

White paper: Digital Car Buyer in Numbers 2022

Unique insights into automotive sector digital, campaign and sales activity.

10.03.2022

Europe’s car brands are sleep-walking into historic levels of marketing inefficiency

Watch part 1 of highlights from the Sophus3 Automotive Digital Summit 2022.

18.11.2021

What automotive can learn from other sectors in digital

DeLu Jackson shares insights as to how car brands can improve their digital performance.

23.07.2021

How to navigate privacy without compromising your analytics

A combination of changes is upending the way car brands can track and interact with users of their digital channels.

17.05.2021

White paper: Rethinking car buying in the ecommerce age

"The results shocked us. Not only did we see variations between the Big 5 markets, but also a patchy performance across the majority of brands, and very few examples of best practice."

22.04.2021

Digital Car Buyer in Numbers 2021

Our annual review of the digital automotive year looks at the impact of the Coronavirus on the automotive industry and the further challenges it faces as the impact of the virus recedes.